Introduction

Almost all Korean medical schools require students to repeat the same year if they fail in even one subject or their grade point average (GPA) is below a certain level. Regulations are strictly enforced, such as the studentŌĆÖs being suspended when they get an F in a course.

In a study of first- and second-year medical students, 17% of students reported that they had already experienced grade repetition [

1]. It is a great loss to individuals, the nation, and society when a significant number of outstanding students fail to succeed in the intense competition of medical schools [

2].

In medical school, assigning an F grade, which indicates grade retention, signifies that neither the school nor the professor assumes responsibility for the studentŌĆÖs failure to meet the learning objectives in that subject and instead places the responsibility solely on that student.

The Accreditation Standards of the Korean Institute of Medical Education and Evaluation 2019 (ASK2019) require medical schools to analyze problems with grade retention and prepare measures to guide students who show poor academic achievement [

3].

To provide interventions for underachievers, it is necessary to identify the predictors of academic achievement, such as the learnerŌĆÖs personality and learning behavioral characteristics including learning strategies [

4-

7]. They were associated with self-assessed academic performance in medical students [

4], and with GPA in health science students in Korea [

5]. Another study also revealed that self-regulating learning strategies could predict the GPA of medical students in Iran [

6].

This study aims to determine whether personality and learning behavioral characteristics are predictors of successful academic achievement among medical students in Korea, specifically the goals of completing medical school without delays and achieving a high GPA in the final year.

Methods

1. Setting, participants, and study design

Gyeongsang National University College of Medicine has collected data (Gyeongsang Medical College Cohort data) on the demographics and academic achievements of all students admitted since 2010 from the universityŌĆÖs computerized information system for medical program evaluation and administrative purposes from 2022.

The Gyeongsang Medical College Cohort provided data of student identification number, sex, admission path, and final school year GPA. Delays in completing medical school were ascertained by reviewing the electronic academic records of each semester enrolled.

This is an observational, retrospective cohort design with a dependent variable of GPA of the final school year. It is a cross-sectional study of delays in completing medical school as a dependent variable because a significant proportion of delays occur before taking the MLST-ŌģĪ test.

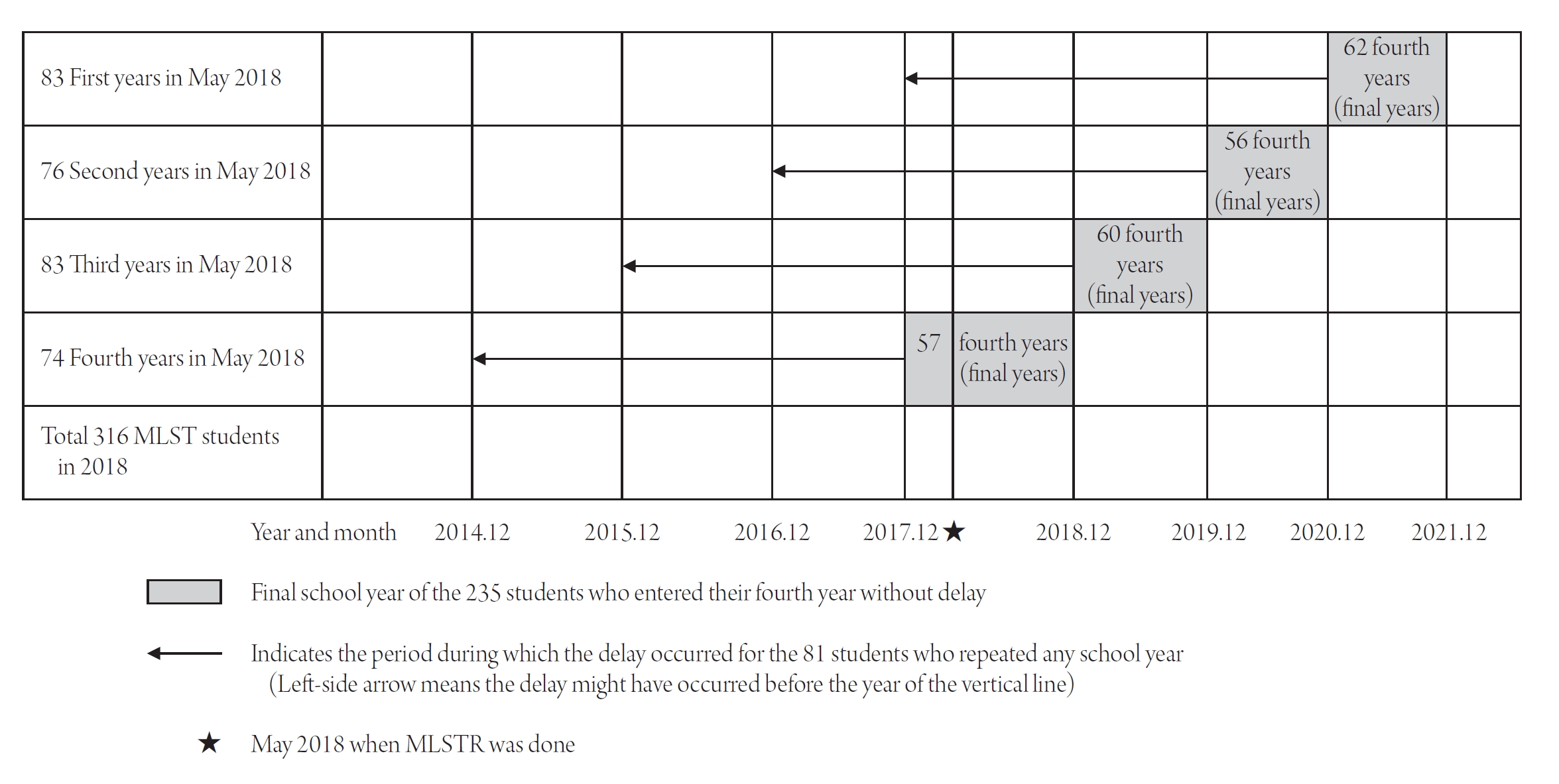

Figure 1 shows the period during which the delay occurred for the 81 of 316 students who repeated any school year and the final school year of the 235 students who entered their fourth year without delay.

The Institutional Review Board of Gyeongsang National University Hospital approved this study (GNUH-IRB 2023-06-016).

2. Variables and measurement tool

Independent variables were student sex, admission path (admission to medical school, transfer to medical school, or admission to a premedical department), personality, and learning behavioral characteristics. The medical studentsŌĆÖ academic achievement was measured by two outcome variables: delays including grade retention or leave of absence in completing medical school and GPA of the final school year.

Personality and learning characteristics were measured with the Multi-Dimensional Learning Strategy Test, 2nd edition (MLST-ŌģĪ) (Inpsyt, Seoul, Korea). Personality characteristics included subscales of academic self-efficacy, outcome expectation, and conscientiousness. High scores indicated initiative in studying [

7]. Learning characteristics included the subscales of time management, listening, note taking, learning environment, concentration, book reading, memory skills, and examination preparation. High scores indicated overall good learning skills [

7]. The score of each subscale was expressed as a T-score (average=50, standard deviation=10) from a standardized test.

All the 316 medical students (83 first-year, 76 second-year, 83 third-year, and 74 fourth-year students) in 2018 took the MLST-ŌģĪ in May after providing informed consent. The test was developed in Korean and aimed to understand the effectiveness of a studentŌĆÖs learning strategy, identify factors that affect learning, and provide suggestions for necessary intervention [

7].

After combining MLST-ŌģĪ test results with the Gyeongsang Medical College Cohort data, the dataset was anonymized.

3. Statistical methods

In a simple analysis, we created cross-tabulations to compare sex, grade, admission path, personality, and learning characteristics depending on delays in completing medical school. The scores of the personality and learning characteristics were categorized into quintiles.

We combined personality and learning behavioral characteristics, each with five categories, to create a new variable with three categories of both low (1 or 2) quintiles, others, and both high (4 or 5) quintiles. p-values were calculated using the Žć2 or Žć2 for a trend test. The adjusted odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of personality and learning behavioral characteristics for completing medical school without delays were also calculated using multiple logistic regression analysis. In this regression model, we included the new combined variable instead of both personality and learning behavioral characteristics as independent variables because of multicollinearity.

For the 235 students completing medical school without delays, we analyzed the associations of sex, admission path, personality, and learning behavioral characteristics with final-year GPA by analysis of variance, or PearsonŌĆÖs correlation analysis. Adjusted regression coefficients of personality and learning behavioral characteristics for GPA of the final school year were calculated using multiple linear regression analysis. Grade was excluded from the models due to its close relationship with the admission path.

All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 25.0 (2017; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Discussion

In this study, learning behavioral characteristics measured with the MLST-ŌģĪ test significantly predicted medical studentsŌĆÖ academic achievements, as assessed by their GPA of the final school year. High scores of learning behavioral characteristics, when combined with high scores of personality characteristics, increased the adjusted odds of completing medical school without delays by 3.6 times. It also significantly predicted the GPA of the final school year after adjusting for sex, admission path, and personality characteristics. The effect was second largest after sex.

Completing medical school without delays needed both the high scores of personality and learning behavioral characteristics, whereas GPA of the final school year only need the high scores of learning behavioral characteristics. Students who experienced delays had an average GPA of 2.85, which was significantly lower than 3.32 for students who did not experience delays (data not shown). Predictors of GPA were analyzed only for the students completing medical school without delays in this study. Regarding delays in completing medical school, the failure experiences were due to both personal and structural factors such as a competitive culture, restrictive professor-student relationships, and indifference toward studentsŌĆÖ quality of life [

2]. In contrast, a high GPA needed mainly personal effort. Completing medical school without delays and achieving a high GPA for the final school year may have different predictors.

Personality characteristics measured with the MLST-ŌģĪ test include subscales of academic self-efficacy, outcome expectation, and conscientiousness, which collectively represent the ability to take the initiative in studying. The subscales of academic self-efficacy and outcome expectation were developed based on social cognitive theory [

7]. A study using a social cognitive framework suggested that self-efficacy and outcome expectation together predict an interest in education [

8].

Personality characteristics or academic self-efficacy alone measured with the MLST-ŌģĪ test affected academic achievement in previous studies among Korean college students [

4,

5,

9].

Low confidence in oneŌĆÖs own abilities will not motivate continuous effort for the desired goal. As a result, the possibility of achieving the desired goal will be low [

7]. Using other measurement tools in other countries, studies found that personality traits including conscientiousness directly and indirectly contributed to the medical studentsŌĆÖ academic performance through self-efficacy [

10]. However, outcome expectation was not a significant component in predicting studentsŌĆÖ academic achievement [

6].

In the MLST-ŌģĪ test used in this study, learning behavioral characteristics, including learning strategies, were composed of the most common and representative learning skills including resource management strategies classified by various studies [

7]. They involved subscales of time management, listening, note taking, learning environment, concentration, book reading, memory skills, and examination preparation.

Learning behavioral characteristics or time management alone measured with the MLST-ŌģĪ test affected academic achievements in previous studies of Korean college students [

4,

5,

9].

Learning strategies including cognitive, metacognitive, and resource management strategies are predictors of studentsŌĆÖ academic achievement [

6]. A literature review concluded that learning skills or strategies were fundamental to academic competence and could be taught [

11].

On the interrelationships between personality, learning behavioral characteristics, and academic achievements, a study using the MLST-ŌģĪ test suggested personality characteristics directly and indirectly affected academic achievements via learning behaviors in the path model [

4].

In this study, we used dependent variables of the GPA of the final school year and delays (grade retention or leave of absence) in completing medical school. MLST-ŌģĪ test results were temporally higher in all study subjects with regard to the GPA of the final school year. However, for the delay in completing medical school, the temporal relationships might be uncertain. For some students, grade retention or leave of absence occurred before taking MLST-ŌģĪ test, which might alter their behavioral characteristics. On the contrary, progression to the next year without repetition could increase self-efficacy for some students. Because this study was performed with students in one medical college in one year, there may be limitations for generalizability.

Because learning behaviors composed of learning skills are modifiable [

11], interventions aimed at correcting them can improve the academic achievements of medical students. To confirm this, we need a randomized controlled trial in future study.

Medical students must learn an enormous amount of information. Learning difficulties among medical students present not only individual academic problems, but also a challenge to current medical education programs. It is necessary to take measures at the school level and not leave the challenge up to the individual students.

This study suggests that individual personality and learning behavior characteristics are predictive factors for medical studentsŌĆÖ academic achievement. Therefore, interventions such as personalized counseling programs should be provided in consideration of these student characteristics.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print