| Korean Med Educ Rev > Volume 26(Suppl1); 2024 > Article |

|

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to explore, using topic modeling, the social value of doctors and medicine demanded by society as reflected in published newspaper articles in Korea. Ultimately, this study aimed to reflect social needs in the process of developing the Patient-Centered DoctorŌĆÖs Competency Framework in Korea. For this purpose, a total of 2,068 newspaper articles published from 2016 to 2020 were analyzed. Through topic modeling of these newspaper articles over the past 5 years, 18 topics were derived and divided into four categories. Focusing on the derived topics and keywords, the topics derived in specific years and the proportion of topics by year were analyzed. The results of this study make it possible to grasp the needs of society projected through the press for doctors and medicine. Due to the nature of the press, topics that frequently appeared in newspaper articles were mainly social phenomena related to requirements for doctors, particularly dealing with economic and legal aspects. In particular, it was confirmed that doctors are now required to have a wider range of competencies that go beyond their required medical knowledge and clinical skills. This study helped to establish doctorsŌĆÖ competencies by analyzing social needs for doctors through the latest research methods, and the findings could help to establish and improve doctorsŌĆÖ competencies through ongoing research in the future.

In the early 20th century, the Flexner Report catalyzed reforms in medical education that emphasized basic science knowledge and prioritized the training of medical education and clinical skills. These reforms laid the groundwork for the modern medical education system. By the 1990s, the concept of physician competencies had become integral to medical education, leading to the definition and incorporation of specific competencies for physicians in many countries [1]. In the United States, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) oversees residency programs and introduced six core competencies in 1999 through the ACGME Outcome Project. These competencies have undergone revisions up until 2019 [2]. Canada undertook the CanMEDS 2000 Project in 1996, a multidisciplinary effort that defined seven key competencies. These have been updated periodically, with the latest iteration being the CanMEDS 2015 Physician Competency Framework [3]. The United Kingdom has maintained four competencies since the General Medical Council established Good Medical Practice in 1995, with updates continuing through to 2019 [4]. Similarly, Korea has defined and developed physician competencies through various studies, including ŌĆ£RESPECT 100, Development of a Generic Curriculum for Graduate Medical Education in Korea (Korean Institute of Medical Education and Evaluation, 2008),ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Survey on General and Specialty Competencies Education and Training in Specialty Boards (Korean Institute of Medical Education and Evaluation, 2012),ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Competency of Residents as Learners and Teachers (Korean Institute of Medical Education and Evaluation, 2013),ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Reorganizing Training Courses by Specialty for the Efficient Training of Specialty Physicians (Korean Academy of Medical Sciences, 2013),ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£Korean doctorŌĆÖs role (Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2014)ŌĆØ [5].

As such, physiciansŌĆÖ competencies have become a critical issue both in Korea and internationally, with a focus on the perspectives of experts and stakeholders in its identification and development. However, the concept of physiciansŌĆÖ competencies is influenced by the political, social, and economic context. Therefore, to establish a relevant definition of physiciansŌĆÖ competencies, it is essential to monitor healthcare-related phenomena in contemporary society and to understand current social issues [1]. This means that physician competence must be viewed through a multifaceted lens that includes political, social, and economic considerations, in addition to professional perspectives. To achieve this, an analysis of the social value of doctors and healthcare as portrayed in the media, such as newspapers and news reports, is necessary. In response to this need, this study aimed to analyze major Korean newspaper articles to assess social demands for physiciansŌĆÖ competencies in the process of developing a framework for ŌĆ£patient-centered physician competencies in Korea,ŌĆØ the first subtask of the ŌĆ£A Study on Improving the System of Graduate Medical Education to Enhance Patient-Centered Performance,ŌĆØ led by Jeon et al. [6] with support from the National Evidence-based Healthcare Collaborating Agency.

Newspapers are the oldest form of mass media [7,8] and have the advantage of reflecting social values and zeitgeist, including the interests and needs of the public [8]. They play a pivotal role in guiding social discourse by highlighting the prevailing interests and issues of the time. In essence, media texts, including newspapers, serve as instruments for the social construction of frames and discourses on specific topics, thereby reflecting the opinions, beliefs, and values of the broader society at that moment [9]. Analyzing newspaper articles through this lens can provide insights into the publicŌĆÖs interest in and perception of the social value of doctors and healthcare. This, in turn, can inform challenges and directions for future research and policy development. Despite this potential, there is a notable absence of studies that have examined the social value of doctors and medical care through media channels such as newspaper articles, underscoring the importance and necessity of such research.

Newspapers represent a vast repository of textual data that record daily events and societal issues over time. Analyzing newspaper articles can reveal trends through time-series data, tracing developments from the past to the present [10,11]. Topic modeling is a useful approach for examining newspaper articles, given their nature. It is a big data analysis technique employed to identify recurring themes within large volumes of unstructured text, such as that found in newspapers [12]. The use of topic modeling to analyze unstructured data is significant because it can uncover new insights or value not obtainable through traditional methods of analyzing structured data [13]. Due to these advantages, topic modeling has been adopted as an analytical tool across various research domains [14].

Therefore, this study explored the social value of doctors and healthcare as perceived and demanded by society by using topic modeling to analyze Korean newspaper articles. Ultimately, the goal of this study is to incorporate t social needs in the process of developing a framework for a patient-centered doctorŌĆÖs competency framework in Korea.

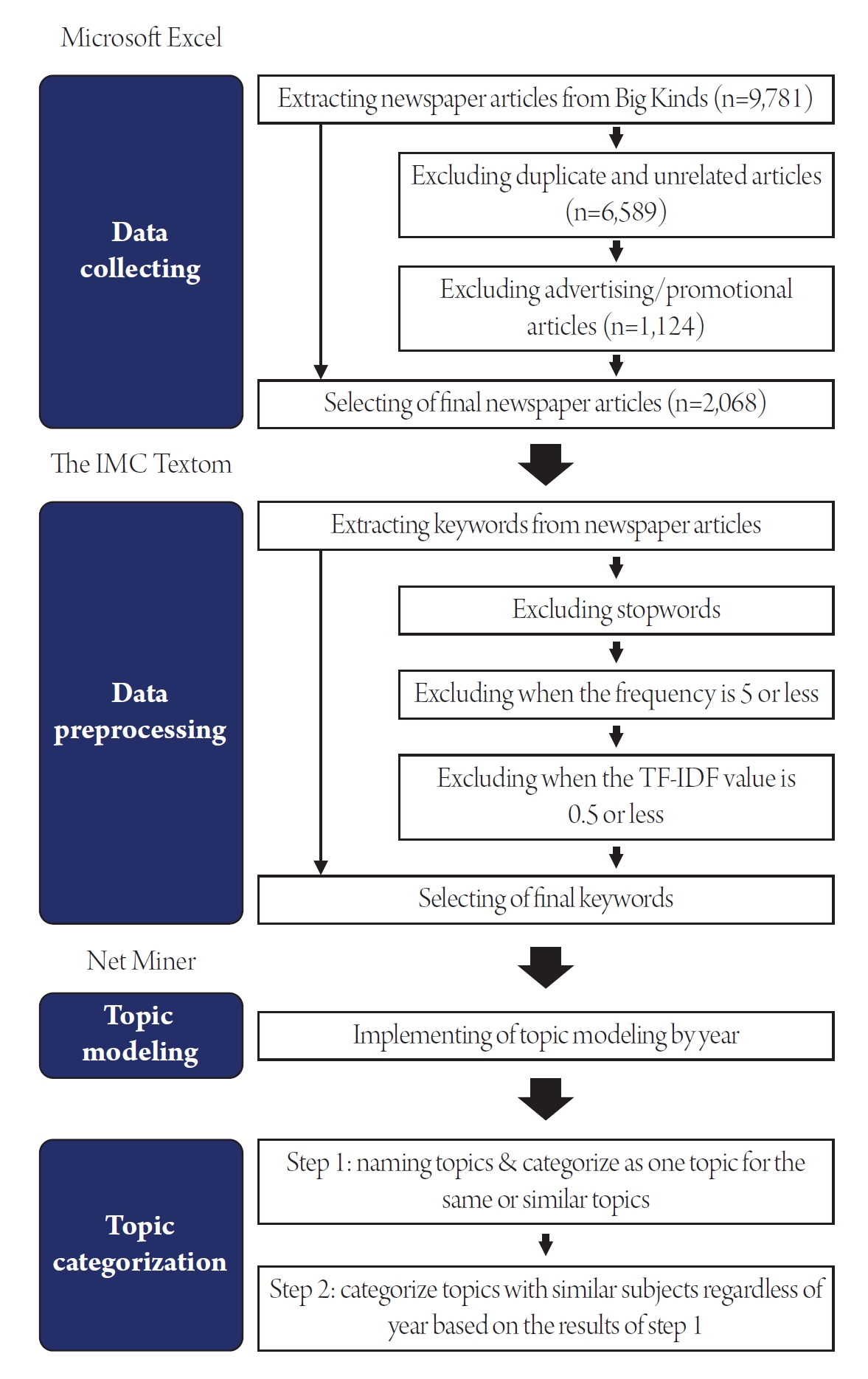

In this study, we collected newspaper articles spanning a recent 5-year period, from January 1, 2016, to December 31, 2020, to conduct topic modeling on physician competencies. We utilized the news trend analysis website Big Kinds (www.bigkinds.or.kr) to search for and retrieve the articles. Big Kinds is a news big data analysis system provided by the Korea Press Foundation. It currently archives and offers access to news from 54 media companies in the form of big data, which facilitates the analysis of a vast quantity of news. Furthermore, Big Kinds allows researchers to tailor their news extraction by setting specific parameters such as the time period, media company, search area, and search method, as well as by inputting relevant search terms. Leveraging these features, we were able to selectively extract the news articles pertinent to our study. The detailed criteria and methodology for the collection are as follows.The study analyzed news outlets including Kyunghyang Shinmun, Kookmin Ilbo, TomorrowŌĆÖs Newspaper, Donga Ilbo, Culture Daily, Seoul Shinmun, World Daily, Chosun Ilbo, JoongAng Ilbo, Hankyoreh, and Hankook Ilbo. These are classified by Big Kinds as 11 major Korean general dailies. We focused on news content provided by Big Kinds, specifically targeting media companies that publish newspaper articles. The search parameters were set to include the terms ŌĆ£doctor AND (competency OR role) AND (medical)ŌĆØ with the search term processing utilizing ŌĆ£morphological analysis.ŌĆØ The search yielded a total of 9,781 newspaper articles, with an annual breakdown as follows: 1,412 articles in 2016, 1,447 in 2017, 1,766 in 2018, 1,724 in 2019, and 3,432 in 2020.

When conducting a morphological analysis search, all articles sharing the same morphology as the entered search term are retrieved, regardless of their subject matter. Consequently, it became necessary to re-categorize the newspaper articles by their titles or topics. In this study, we removed duplicates and irrelevant articles from the initial collection obtained through Big Kinds, using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA). A total of 6,589 newspaper articles were discarded. Additionally, we eliminated 1,124 articles that were advertisements or promotional in nature. Ultimately, we analyzed a total of 2,068 newspaper articles, which included 378 from 2016, 294 from 2017, 371 from 2018, 432 from 2019, and 593 from 2020.

Since the collected newspaper articles consist of text sentences and paragraphs, keyword analysis necessitates a data preprocessing step to break down the data into individual words, rendering them suitable for analysis. To this end, the current study undertook data preprocessing to extract keywords that not only encapsulate the societal demand for doctors and medical care as depicted in the newspaper articles but are also compatible with the input requirements of the analysis program. We utilized the IMC Textom, a web-based big data analysis program developed by The IMC Inc. in Daegu, Korea, for this data preprocessing task. Textom was selected for its efficiency in word extraction, particularly its feature that automatically transforms verb forms into their corresponding noun forms. In our study, data preprocessing involved conducting detailed morphological analysis and text mining using the functionalities provided by Textom.

In some instances, the words extracted by Textstorm may accurately reflect the content of the newspaper article, yet their grammatical form is that of a verb rather than a noun, or they fail to meaningfully describe the articleŌĆÖs content. In our study, we utilized TextomŌĆÖs automation feature to convert words from their verb form to nouns. Additionally, we eliminated stopwords from the extracted words. These stopwords include conjunctions, prepositions, adverbs, and articles that lack specific meaning, as well as noun-type words that do not convey meaningful content. Examples of such stopwords are ŌĆ£however,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£like,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£one after another,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£on the contrary,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£this,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£those.ŌĆØ Lastly, we excluded words that appeared fewer than 5 times from our study, as their infrequent occurrence may not provide a clear indication of overarching trends.

Words with low term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) values were removed. TF-IDF is not simply a measure of word frequency across all newspaper articles; it gauges how often a word appears in a specific article relative to a corpus. This metric reflects the relevance of a word to a single document or topic. A low TF-IDF score indicates that a word is common across all documents in the corpus, making it less useful for describing a specific topic due to its ubiquity. Conversely, a high TF-IDF score signifies that a word is frequent in a particular document but rare in others. In essence, the more common a word is across all documents, the higher its TF-IDF score will be, and the closer the score is to zero, the more common the word is. For this study, we set the threshold for TF-IDF at 0.5 or lower. Additionally, we standardized terms with the same meaning but different forms among the derived words.

To extract specific topics, we conducted topic modeling on the final selection of keywords following data preprocessing. Topic modeling is an analytical technique that uncovers the relationships between words within large-scale documents and derives structured topics. This technique encompasses methods such as latent semantic analysis, probabilistic latent semantic analysis, and latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA), with LDA being the most widely recognized topic model [15]. Recently, there has been a surge in research papers employing LDA techniques within the realm of medical education [16-18]. LDA topic modeling identifies the extent to which words in one newspaper article co-occur in others, as well as the intermediary relationships between these words. It clusters words that meet the researcher-defined criteria and designates them as a topic group if they are deemed representative of a specific topic. In our study, we applied topic modeling to newspaper articles from 2016 to 2020, categorizing topics related to societal needs for physicians and medical services based on the words identified post-data preprocessing. The topic modeling was executed using the Net Miner ver. 4.2 software (Cyram Inc., Seongnam, Korea).

The topics identified by year through topic modeling were categorized in two steps, all of which involved discussion by the researcher. In Step 1, categorization occurred on an annual basis. For each year, the researcher assigned names to each topic through discussion, and topics that were the same or similar were grouped together as a single topic. Step 2 involved categorization based on the outcomes of Step 1, grouping together topics with similar themes across different years. The research process is illustrated in Figure 1.

From January 1, 2016, to December 31, 2020, a total of 2,068 newspaper articles related to the competence and role of physicians were published: 378 in 2016, 294 in 2017, 371 in 2018, 432 in 2019, and 593 in 2020 (Table 1). Topic modeling performed on these articles yielded 10 topics in 2016, nine topics in both 2017 and 2018, 11 topics in 2019, and 13 topics in 2020. When the topics identified through topic modeling shared similar keywords or themes, they were combined and categorized for each respective year. Consequently, eight topics were selected for 2016, seven for 2017, six for 2018, eight for 2019, and nine for 2020. The finalized topics were then assigned appropriate names.

The eight topics identified in 2016 were ŌĆ£digital healthcare,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£healthcare system,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£communicable disease control,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£medical technology,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£global healthcare,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£publicness in healthcare,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£medical volunteering,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£patient safety.ŌĆØ The seven topics identified in 2017 were ŌĆ£patient safety,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£medical volunteering,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£publicness in healthcare,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£palliative care,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£convergence,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£healthcare system,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£digital healthcare.ŌĆØ In 2018, the six topics were ŌĆ£digital healthcare,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£healthcare system,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£patient-centeredness and good doctors,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£publicness in healthcare,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£medical science research,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£global healthcare.ŌĆØ In 2019, the eight topics were ŌĆ£digital healthcare,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£medical technology,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£publicness in healthcare,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£patient safety,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£global healthcare,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£healthcare policy,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£medical volunteering,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£palliative care.ŌĆØ Finally, the nine topics that emerged in 2020 were ŌĆ£digital healthcare,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£publicness in healthcare,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£conflict between medical professionals and the government,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£COVID-19: telemedicine,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£telemedicine,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£medical volunteering,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£healthcare policy,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£COVID-19: lack of medical resources,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£COVID-19: dedication of medical staff.ŌĆØ

As shown above, a total of 18 topics have been identified over the past 5 years. These topics are ŌĆ£digital healthcare,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£communicable disease control,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£medical technology,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£global healthcare,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£publicness in healthcare,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£medical volunteering,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£patient safety,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£palliative care,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£convergence,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£healthcare system,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£patient-centeredness and good doctors,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£medical science research,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£healthcare policy,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£conflict between medical professionals and the government,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£telemedicine,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£COVID-19: lack of medical resources,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£COVID-19: dedication of medical staff,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£COVID-19: telemedicine.ŌĆØ Among these, ŌĆ£digital healthcareŌĆØ and ŌĆ£publicness in healthcareŌĆØ have been the most consistently discussed topics over the 5-year period. In contrast, certain topics emerged in specific years: ŌĆ£communicable disease controlŌĆØ appeared in 2016, ŌĆ£convergenceŌĆØ in 2017, ŌĆ£patient-centeredness and good doctorsŌĆØ and ŌĆ£medical science researchŌĆØ in 2018, and ŌĆ£conflict between medical professionals and the government,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£telemedicine,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£COVID-19: lack of medical resources,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£COVID-19: dedication of medical staff,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£COVID-19: telemedicineŌĆØ in 2020.

The 18 topics were grouped into four categories based on their similarities: healthcare industry, healthcare policy, patient-centered medicine, and infectious diseases. Specifically, the topics ŌĆ£digital healthcare,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£global healthcare,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£medical technology,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£convergence,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£medical science research,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£telemedicineŌĆØ were categorized under ŌĆ£healthcare industry.ŌĆØ The topics ŌĆ£publicness in healthcare,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£healthcare system,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£healthcare policy,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£conflict between medical professionals and the governmentŌĆØ were grouped under ŌĆ£healthcare policy.ŌĆØ The topics ŌĆ£medical volunteering,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£patient safety,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£palliative medicine,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£patient-centeredness,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£good doctorsŌĆØ were classified as ŌĆ£patient-centered medicine.ŌĆØ Lastly, ŌĆ£communicable disease control,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£COVID-19: lack of medical resources,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£COVID-19: dedication of medical staff,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£COVID-19: telemedicineŌĆØ were categorized as ŌĆ£infectious diseases.ŌĆØ

The main keywords for each topic are listed below (Appendix 1). The topics identified for the 5-year period from 2016 to 2020 are ŌĆ£digital healthcareŌĆØ and ŌĆ£publicness in healthcare.ŌĆØ The main keywords for ŌĆ£digital healthcareŌĆØ are summarized as follows: ŌĆ£Watson,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£diagnostics,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£platform,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£artificial intelligence (AI),ŌĆØ ŌĆ£data,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£precision,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£advanced,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£convergence,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£internet of things (IoT),ŌĆØ ŌĆ£hub,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£robotics,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£healthcare,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£personalized,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£smart,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£video,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£augmented reality,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£reading,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£telemedicine,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£big data,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£prediction,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£digital healthcare,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£innovation,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£digital,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£remote work,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£deep learning,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Industry 4.0.ŌĆØ The keywords for ŌĆ£publicness in healthcareŌĆØ include ŌĆ£public medical school,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£establishment,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£public,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£universal,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£workforce,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£public healthcare,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£elderly,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£long-term care,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£dementia,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£welfare,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£dementia care,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£for-profit,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£medical welfare,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£healthcare disparities,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£public health scholarships,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£vulnerable,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£strike,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£resident,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£medical association,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£local government,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£private.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£Medical volunteeringŌĆØ was identified in 4 years, with the exception of 2018, and the main keywords were ŌĆ£mission,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£service,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£doctors without borders,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Africa,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£religion,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£medical service,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£relief,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£free,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£overseas,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£free hospital,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£welfare center,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Bangladesh,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£refugee,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£poor,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£donation,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Gambia,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Vietnam,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£rural,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Ethiopia,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Morocco,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Tae-Seok Lee,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Afghanistan,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£heart center,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£poverty,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£Cambodia.ŌĆØ

The topics that emerged in 3 years were ŌĆ£healthcare system,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£patient safety,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£global healthcare.ŌĆØ The main keywords for ŌĆ£healthcare systemŌĆØ from 2016 to 2018 were ŌĆ£rural,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£health center,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£medicine,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£facility,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£network,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£service,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£community care,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£primary care,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£health,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£healthcare,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£national primary care,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£prevention,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£dementia,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£long-term care,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£elderly,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£primary care system,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£home visits,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£nursing home,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£public guardianship,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£national accountability system,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£neighborhood doctor.ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Patient safetyŌĆØ is a topic that emerged in 2016, 2017, and 2019, with the following keywords: ŌĆ£mediation,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£dispute,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£arbitration,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£accident,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£lawsuit,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£proceeding,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£discipline,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£arbitrator,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£negligence,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£civil,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£judgment,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£suspension,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£disposition,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£show doctor,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Namki Baek,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£illegal,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£death,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£medicine,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£violation,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£medical law,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£ethics,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£medical dispute,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£unlicensed,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£court,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£illegal procedure,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£bioethics,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£manipulation,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£professional ethics,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£surrogate surgery,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£abortion,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£license.ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Global healthcareŌĆØ was derived in 2016, 2018, and 2019, and the keywords are: ŌĆ£advance,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£world,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£leading,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£market,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£attract,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£global,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£overseas,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£medical tourism,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£China,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£network,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Mongolia,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£agreement,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£exchange,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Southeast Asia,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£underdeveloped,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£spread,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Russia,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£medical export,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£training,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Korean Wave,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£visit,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£medical market,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£international patients,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£United States,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Myanmar,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Bahrain,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Middle East,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£tourism,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Uzbekistan,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Zambia,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£Bangladesh.ŌĆØ

The topics identified in 2 years were ŌĆ£medical technology,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£palliative care,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£healthcare policy.ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Medical technologyŌĆØ was identified in 2016 and 2019, with keywords including: ŌĆ£endoscopy,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£wearable,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£medical device,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£precision,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£lesion location,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£minimally invasive,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£laparoscopic,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£regenerative,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£procedure,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£transplant,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£biomarker,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£cochlear implant,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£face lift surgery,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£bionic,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£trauma center,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£gastrectomy,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£tumor.ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Palliative careŌĆØ was derived in 2017 and 2019, with the following keywords: ŌĆ£hospice,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£death preparation,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£death,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£terminal cancer,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£palliative care,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£cessation,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Life-sustaining treatment,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£euthanasia,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£dignity,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£end of life,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£palliative,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£terminal.ŌĆØ ŌĆ£ConvergenceŌĆØ is a topic that only emerged in 2017, with keywords including ŌĆ£MERS,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£infectious disease,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£response,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£measures,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£countermeasures,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£inadequacies,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£public health system.ŌĆØ In 2019 and 2020, the main keywords for ŌĆ£healthcare policyŌĆØ were ŌĆ£public,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£health insurance,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£medical fee,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£public health,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£institution,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£critical care center,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£health insurance premium,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£medical helicopter,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£cooperative,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£hospitalist,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£emergency room,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£vulnerable,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£Medicare.ŌĆØ

The topics identified in a single year were ŌĆ£communicable disease control,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£patient centeredness and good doctors,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£medical science research,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£conflict between medical professionals and the government,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£telemedicine,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£COVID-19: lack of medical resources,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£COVID-19: dedication of medical staff,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£COVID-19: telemedicine.ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Communicable disease controlŌĆØ is a topic that was only identified in 2016, and it included keywords related to the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) outbreak in 2015, with the following main keywords: ŌĆ£MERS,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£infectious disease,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£response,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£measures,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£countermeasures,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£inadequacies,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£public health system.ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Patient-centered and good doctorsŌĆØ and ŌĆ£medical researchŌĆØ were derived only in 2018. The main keywords of ŌĆ£patient-centered and good doctorsŌĆØ were ŌĆ£total care,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£patient-centered,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£safety,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£communication,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£good doctors,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£medical quality,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£personalized care,ŌĆØ and the main keywords of ŌĆ£medical science researchŌĆØ were ŌĆ£scientist,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£training,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£research and development,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£research doctor,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£research-oriented hospital,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£technology development,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£multidisciplinary.ŌĆØ

The topics that emerged in 2020 alone were: ŌĆ£Conflict between medical professionals and the government,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£telemedicine,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£COVID-19: lack of medical resources,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£COVID-19: dedication of medical staff,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£COVID-19: telemedicine.ŌĆØ The main keywords of ŌĆ£conflict between medical professionals and the governmentŌĆØ were ŌĆ£collective leave,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£strike,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£collective action,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£residents,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£medical association,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£gap,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£agitation,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£examination,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£refusal.ŌĆØ The main keywords of the ŌĆ£telemedicineŌĆØ were ŌĆ£remote,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£industry,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£digital,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£online,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£sensors.ŌĆØ In 2020, three topics related to COVID-19 emerged. The main keywords for ŌĆ£COVID-19: lack of medical resourcesŌĆØ were ŌĆ£medical staff,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£lack,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£gap,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£urgent,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£beds,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£workforce,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£limits,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£financial difficulties,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£burnoutŌĆØ; those for ŌĆ£COVID-19: dedication of medical staffŌĆØ were ŌĆ£sacrifice,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£dedication,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£service,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£medical staff,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£medical volunteering,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£voluntary,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£workforce,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£lack,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£urgent,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£collaboration,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£cooperation,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£dispatch,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£supportŌĆØ; and those for ŌĆ£COVID-19: telemedicineŌĆØ were ŌĆ£remote,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£telemedicine,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£contactless,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£diagnosis,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£regulation,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£permission,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£information and communication technology (ICT),ŌĆØ ŌĆ£response,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£infection,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£safety.ŌĆØ

The distribution of topics by year from 2016 to 2020 is presented in Table 1. In 2016, the category with the highest number of newspaper articles was ŌĆ£medical technology,ŌĆØ accounting for 77 articles, or 20.4% of the total. The topic ŌĆ£communicable disease controlŌĆØ was unique to 2016, comprising 58 articles (15.3%) that were associated with the 2015 MERS outbreak. The concept of ŌĆ£publicness in healthcareŌĆØ was consistently explored from 2016 to 2020, with key issues encompassing public healthcare, the creation of public medical schools, and the public health scholarship program. In terms of public healthcare, the government unveiled the Public Healthcare Implementation Plan and Public Healthcare Plan in 2016, followed by the Comprehensive Plan for the Development of Public Healthcare in 2018. These initiatives aimed to bolster national accountability for public healthcare and to mitigate regional disparities in access to essential medical services. Subsequently, media coverage highlighted these regional disparities, focusing on essential healthcare, public healthcare, and medical services. Notably, in 2018, articles pertaining to ŌĆ£publicness in healthcareŌĆØ accounted for 18.1% of the total, a higher proportion than in other years. This surge can be attributed to the heightened coverage of conflicts between healthcare professionals and the government during that time. The governmentŌĆÖs proposal to establish a national public medical college, intended to alleviate the workforce shortage in essential healthcare, was met with resistance from medical professionals, resulting in noteworthy discord.

Among the seven topics identified in 2017, ŌĆ£digital healthcareŌĆØ (63, 21.4%) and ŌĆ£convergenceŌĆØ (59, 20.1%) had the highest proportions. Notably, the share of ŌĆ£digital healthcareŌĆØ topics saw a significant increase of 6.3% points, rising from 15.1% in 2016 to 21.4% in 2017. This surge can be attributed to the deployment of the artificial intelligence system ŌĆ£Watson for OncologyŌĆØ (Watson) by Gachon University Gil Hospital in December 2016, which spurred a substantial number of related articles the following year. Furthermore, the category of ŌĆ£convergenceŌĆØ emerged exclusively in 2017. This emergence is likely linked to the integration of Watson into digital healthcare, suggesting the potential for blending multidisciplinary care and collaboration, as well as merging medicine and information technology.

The topics ŌĆ£patient-centeredness and good doctorsŌĆØ (48 articles, 12.9%) and ŌĆ£medical science researchŌĆØ (36 articles, 9.7%) were only identified in 2018 and are associated with initiatives launched by the government that year. Specifically, the government announced the Patient-centered Medical Technology Optimization Research Project and the Strategy for Fostering Research Doctors and Hospital Innovation. It appears that articles related to these projects were prominently featured in 2018. Furthermore, there was a notable increase in articles pertaining to ŌĆ£global healthcare,ŌĆØ rising from 11.4% in 2016 to 21.0% in 2018. This surge can be seen as a response to a press release from the Ministry of Health and Welfare, which reported an uptick in the number of foreign patients visiting Korea in 2018.

ŌĆ£Palliative careŌĆØ appeared as a topic in 2017 (28 cases, 9.5%) and 2019 (34 cases, 7.9%). These years correspond to significant legislative milestones in the realm of hospice and palliative care, as well as decisions regarding life-sustaining treatment for end-of-life patients. Specifically, a law was enacted on August 4, 2017, and subsequently underwent a partial amendment on March 28, 2019. This legislative activity likely accounts for the increased attention to palliative care in scholarly articles during 2017 and 2019.

In 2020, the landscape of healthcare and the challenges faced by doctors were unlike any other year. After the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed in South Korea, a continuous stream of issues related to the pandemic emerged. Additionally, there were significant disruptions such as collective leave taken by medical professionals due to disputes with the government, resident physician strikes, medical students jointly suspending their studies, and boycotts of the medical licensing examination. Consequently, the most prominent topics related to COVID-19 were ŌĆ£COVID-19: lack of medical resourcesŌĆØ (97 mentions, 16.4%), ŌĆ£COVID-19: dedication of medical staffŌĆØ (84 mentions, 14.2%), and ŌĆ£COVID-19: telemedicineŌĆØ (86 mentions, 14.5%). These topics stood out in frequency when compared to other issues.

To cultivate the doctors needed for society and to train them properly, it is necessary to establish appropriate competencies for physicians. The shift toward competency-based, performance-oriented training systems for residents necessitates the precise definition of these competencies. With this objective in mind, the patient-centered physician competencies in Korea framework was developed in 2021, supported by the Korea Healthcare Research Institute [6]. As part of the development of this framework, this study employed topic modeling to analyze major Korean newspaper articles. This analysis aimed to capture the expectations and requirements of Korean society regarding doctors and medical care, and the findings were incorporated into the competency framework for doctors.

Based on an analysis of major Korean newspaper articles from the past 5 years, spanning 2016 to 2020, we have identified societal expectations of doctors and healthcare as reflected in these publications. Given the mediaŌĆÖs focus, many of the topics discussed in the articles centered on social phenomena, including the expectations placed on doctors, and also covered a range of economic and legal issues.

Topic modeling yielded 18 distinct topics over a 5-year period. We examined the primary keywords associated with each topic and tracked the prevalence of these topics annually. Our analysis of the main keywords revealed an increasing expectation for doctors to possess a broader range of competencies beyond the essential medical knowledge and clinical skills traditionally required. The necessity for doctors to acquire a diverse set of competencies, in addition to foundational skills, has been previously addressed in the literature, and various countries have proposed frameworks for what constitutes basic competencies for physicians [2-4,19,20].

The core competencies of patient-centered physicians in Korea relate to the physicianŌĆÖs role as an expert, communicator, collaborator, healthcare leader, professional, and scholar. Based on these core competencies, 15 of the 18 identified topics can be included in the competencies of healthcare leaders, professionals, and communicators. Eleven of the topics (ŌĆ£digital healthcare,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£global healthcare,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£telemedicine,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£publicness in healthcare,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£healthcare system,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£healthcare policy,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£conflict between medical professionals and the government,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£communicable disease control,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£COVID-19: lack of medical resources,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£COVID-19: dedication of medical staff,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£COVID-19: telemedicineŌĆØ) could be included in the competencies of healthcare leaders, four of the topics (ŌĆ£healthcare technology,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£patient safety,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£palliative care,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£patient centeredness and good doctorsŌĆØ) could be included in the competencies of professionals, and two of the topics (ŌĆ£palliative care,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£patient centeredness and good doctorsŌĆØ) could be included in the competencies of communicators. These findings are similar to previous studies that have shown that the publicŌĆÖs expectations and satisfaction with doctorsŌĆÖ social competencies include poor communication skills with patients and caregivers and lower-than-normal ratings of leadership skills and responsibility as a member of society [21].

In addition, three of the 18 topicsŌĆöŌĆ£convergence,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£medical science research,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£medical volunteeringŌĆØŌĆöwere found to be socially relevant issues, which can be judged as reflecting social demands for doctors and medical care. In addition, these topics are included in doctorsŌĆÖ competencies in terms of content, but they are not included in the core competencies and detailed competencies of the Korean patient-centered physician competencies. The reason for this exclusion is that the defined competencies of doctors are restricted to the core competencies that all physicians should possess and to areas that are amenable to education and evaluation. It is anticipated that the inclusion of these topics in the competency framework could be reconsidered following further research.

Over the 5-year period from 2016 to 2020, ŌĆ£digital healthcareŌĆØ and ŌĆ£publicness in healthcareŌĆØ were identified as topics each year. Digital healthcare, being closely linked to industrial potential as well as the health and lives of people, has received significant government attention. In response, the government has developed an industrial policy and implemented various strategies, including the 2017 Healthcare Development Strategy, which is aligned with the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Consequently, digital healthcare has been frequently featured in newspaper reports. Publicness in healthcare has gained increased media attention, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. This concept focuses on reducing health and healthcare utilization inequalities by addressing gaps in healthcare for medically vulnerable populations and regions. It also aims to establish a safety net capable of effectively responding to national disasters, catastrophes, and emergencies. In the patient-centered doctorŌĆÖs competency framework in Korea, digital healthcare is incorporated as a sub-competency under the core competencies of healthcare leaders, preparing them for future changes. Similarly, publicness in healthcare is addressed within the sub-competencies of social activities for promoting health and enhancing equity in healthcare.

The 18 topics were analyzed based on the proportion of topics that emerged each year, along with keywords associated with policies or projects implemented in that year, or issues that arose within the medical field. Given the nature of newspapers to reflect contemporary social issues and political challenges, it is not feasible to precisely determine the competencies society expects from doctors through keyword analysis of newspaper articles [22]. However, it is important to pay attention to the topics identified in newspaper articles, particularly those that have persisted over an extended period, those that have faded without resolution, or those that are newly emerging. This analysis can provide insight into the issues that doctors should be aware of within society and the social phenomena currently affecting the Korean medical community. It can also stimulate and refine discourse on doctorsŌĆÖ potential roles in society.

The importance of this discussion is heightened in the information age, where the general public frequently acquires medical knowledge through newspaper articles, news broadcasts, and social networking services (SNS). Consequently, there is an increasing need for physicians to engage with a variety of societal issues and phenomena [23-26]. With the rise in smartphone usage and the proliferation of social media, it has become crucial for doctors to communicate not only with individual patients but also with the wider public and media outlets [27,28]. Effective communication with society at large is now recognized as a key competency for physicians. Specifically, doctors should serve as informed experts who can evaluate various media content using their professional knowledge, helping to prevent the spread of indiscriminate or biased medical information. This necessitates discussions and education regarding the roles doctors can play within society.

Limitations of this study include the fact that we analyzed newspaper articles over a 5-year period from 2016 to 2020, that we were unable to analyze all newspapers in Korea, and that the categorization of topics was based on the subjective views of the researchers.

This study was conducted to examine the feasibility of the competency-oriented, outcome-based patient-centered doctorŌĆÖs competency framework in Korea, which was developed to improve the resident training system. This study used cutting-edge research methods to explore the societal demands for physicians using a variety of media to help define the competencies of physicians. Continued research on this topic can help define and improve the competencies of physicians needed in the future. Furthermore, the physician competencies explored in this study can be used as evidence for the development of medical education curricula.

NOTES

Table┬Ā1.

The proportion of topics by year

REFERENCES

1. Albanese MA, Mejicano G, Mullan P, Kokotailo P, Gruppen L. Defining characteristics of educational competencies. Med Educ. 2008;42(3):248-55. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02996.x

2. Edgar L, McLean S, Hogan SO, Hamstra S, Holmboe ES. The Milestones guidebook. Chicago (IL): Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; 2020.

3. Frank JR, Snell L, Sherbino J. CanMEDS 2015 Physician Competency Framework. Ottawa (ON): Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2015.

4. General Medical Council. Good Medical Practice. London: General Medical Council; 2020.

5. Lee SW. Concept and development of resident training program for general competencies. Korean Med Educ Rev. 2017;19(2):63-9. https://doi.org/10.17496/kmer.2017.19.2.63

6. Jeon WT, Jung H, Kim YJ, Kim C, Yune S, Lee GH, et al. Patient-centered doctorŌĆÖs competency framework in Korea. Korean Med Educ Rev. 2022;24(2):79-92. https://doi.org/10.17496/kmer.2022.24.2.79

7. Jung YJ, Kim JH, Yoo JW. Research on the process to a popularization of dancesports through the mass media. Korea J Physi Educ. 2003;42(3):355-64.

8. Kim HK. A study on the social recognition of library [dissertation]. Seoul: Chung-Ang University; 2011.

9. Clarke J. Portrayal of childhood cancer in English language magazines in North America: 1970-2001. J Health Commun. 2005;10(7):593-607. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730500267605

10. Na K, Lee J. Trends of South KoreaŌĆÖs informatization and librariesŌĆÖ role based on newspaper big data. J Korea Contents Assoc. 2018;18(9):14-33. https://doi.org/10.5392/JKCA.2018.18.09.014

11. Han S. An analysis of news trends for libraries in Korea: based on 1990-2018 news big data. J Korean Soc Inf Manag. 2019;36(3):7-36. https://doi.org/10.3743/KOSIM.2019.36.3.007

12. Cho KW, Bae SK, Woo YW. Analysis on topic trends and topic modeling of KSHSM Journal papers using text mining. Korean J Health Serv Manag. 2017;11(4):213-24. https://doi.org/10.12811/kshsm.2017.11.4.213

13. Yang YH. Analysis on types and trends of public conflicts using topic modeling. Korea Local Adm Rev. 2021;35(2):159-88. https://doi.org/10.20484/klog.23.3.18

14. Kang B, Song M, Jho W. A study on opinion mining of newspaper texts based on topic modeling. J Korean Soc Libr Inf Sci. 2013;47(4):315-34. https://doi.org/10.4275/KSLIS.2013.47.4.315

16. Zhang R, Pakhomov S, Gladding S, Aylward M, Borman-Shoap E, Melton GB. Automated assessment of medical training evaluation text. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2012;2012:1459-68.

17. Borakati A. Evaluation of an international medical E-learning course with natural language processing and machine learning. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):181. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02609-8

18. Moon H, Kim S, Lee J, Cheon J. Examination of change in perception toward virtual medical education after COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S. using Twitter data. Proceeding of the Annual Convention of the Association for Educational Communications and Technology; 2021 Nov 2-6; Chicago, USA. Bloomington (IN): Association for Educational Communications and Technology; 2021. p. 172-80.

19. Carraccio C, Wolfsthal SD, Englander R, Ferentz K, Martin C. Shifting paradigms: from Flexner to competencies. Acad Med. 2002;77(5):361-7. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200205000-00003

20. Shah N, Desai C, Jorwekar G, Badyal D, Singh T. Competency-based medical education: an overview and application in pharmacology. Indian J Pharmacol. 2016;48(Suppl 1):S5-9. https://doi.org/10.4103/0253-7613.193312

21. Heo YJ. DoctorsŌĆÖ competency and empowerment measures desired by the state and society. J Korean Med Assoc. 2014;57(2):121-7. https://doi.org/10.5124/jkma.2014.57.2.121

22. Collins PA, Abelson J, Pyman H, Lavis JN. Are we expecting too much from print media?: an analysis of newspaper coverage of the 2002 Canadian healthcare reform debate. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(1):89-102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.12.012

23. Dutta-Bergman MJ. Primary sources of health information: comparisons in the domain of health attitudes, health cognitions, and health behaviors. Health Commun. 2004;16(3):273-88. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327027HC1603_1

24. Dutta-Bergman MJ. Developing a profile of consumer intention to seek out additional information beyond a doctor: the role of communicative and motivation variables. Health Commun. 2005;17(1):1-16. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327027hc1701_1

25. Prosser H. Marvelous medicines and dangerous drugs: the representation of prescription medicine in the UK newsprint media. Public Underst Sci. 2010;19(1):52-69. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662508094100

26. Furstrand D, Pihl A, Orbe EB, Kingod N, Sondergaard J. ŌĆ£Ask a doctor about coronavirusŌĆØ: how physicians on social media can provide valid health information during a pandemic. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(4):e24586. https://doi.org/10.2196/24586

27. Kim CJ, Kwon I, Han HJ, Heo YJ, Ahn D. Korean doctorsŌĆÖ perception on doctorŌĆÖs social competency: based on a survey on doctors. J Korean Med Assoc. 2014;57(2):128-36. https://doi.org/10.5124/jkma.2014.57.2.128

28. Smailhodzic E, Hooijsma W, Boonstra A, Langley DJ. Social media use in healthcare: a systematic review of effects on patients and on their relationship with healthcare professionals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):442. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1691-0

-

METRICS

-

- 0 Crossref

- 0 Scopus

- 835 View

- 17 Download

- ORCID iDs

-

Hanna Jung

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5051-3953Jea Woog Lee

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8112-407XGeon Ho Lee

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0696-3804 - Related articles

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print